Tom Morandi is a distinguished American sculptor and educator whose work has significantly shaped Oregon’s public art landscape. After receiving his early education at Indiana State Teachers College (now Indiana University of Pennsylvania), he earned his MFA in sculpture from Ohio University. In the early 1970s, Morandi moved to Oregon, where he joined the faculty at Eastern Oregon State Teachers College (now Eastern Oregon University) in La Grande. He later became a Tenured Professor at Oregon State University.

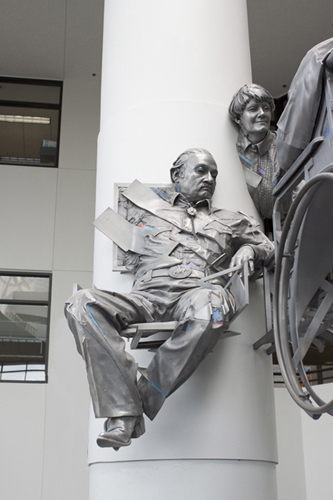

Morandi is perhaps best known for creating “November Sprinter” (1976), a monumental bronze sculpture at the Oregon State Capitol’s east entrance. This piece was one of the first major commissions under Oregon’s pioneering Percent for Art program. His other notable public works include the Sprague Fountain in Salem, created in collaboration with sculptor Bill Blicks, a 25-foot bronze tribute to timber workers in Aberdeen, and a series of life-cast sculptures of sports fans at Oregon State University’s Reser Stadium.

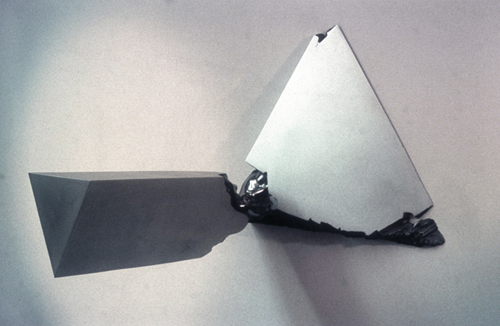

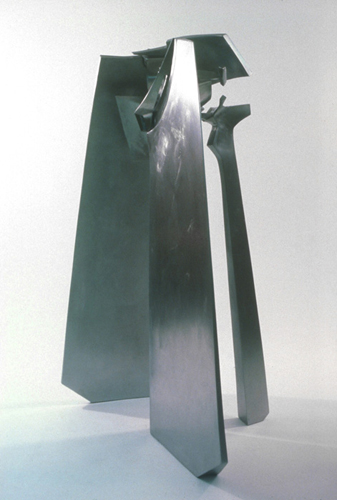

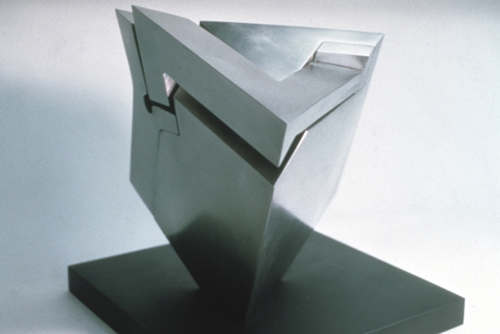

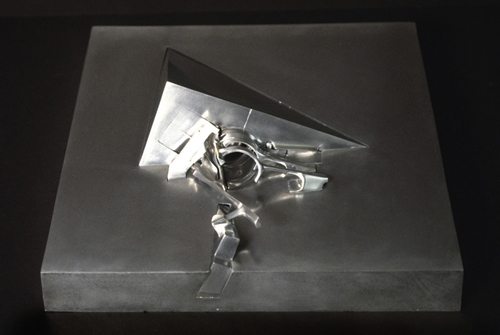

Throughout his career, Morandi has worked primarily in bronze and steel, developing innovative casting techniques that allowed him to create larger, thinner bronze pieces than conventional methods permitted. His work evolved from abstract forms focusing on “strength and grace” to more figurative pieces in the late 1980s, always maintaining a strong connection to community and place.

As an educator, Morandi balanced teaching with his artistic practice, inspiring generations of students while maintaining an active studio practice. His approach to public art, characterized by meticulous craftsmanship and a deep understanding of materials, has left an enduring mark on the Pacific Northwest’s artistic heritage.

Oral History Interview with Tom Morandi

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OaAU94hY1nM

Interviewer: Morgan Young

Project: Oregon State Capitol Foundation Oral History Project

Date: June 27, 2024

Location: His home in Corvallis, Oregon

TRANSCRIPT OF INTERVIEW

Young: Thanks for being with us this afternoon.

Morandi: I’m pleased to be here. Thank you for coming.

Young: I want to start with just framing our discussion. We’ll be primarily about two pieces you’ve done in Salem – November Sprinter and then the fountain. But I want to go back further and have you tell me a bit about your early life and what eventually drew you to the arts.

Morandi: When I was just a very little boy, I was firstborn and I guess I must have been bored because my mother sat me down at the kitchen table and to amuse me she took a piece of paper and a pencil and she said, “Watch this, Tommy,” and with two or three lines boldly placed – bang! There was a face. It was magic. I mean, it truly was. I felt it was magic. How did she do that? Then she drew another and another, and for me it was the most fascinating thing I’d ever seen. And I guess when you ask where my interest began, that would be it.

Looking further along, art – no art classes in particular through high school – was the only thing that engaged me. I mean, I did okay in my other classes, but the class I looked forward to was art class. And when I graduated, I recall my father taking me aside and said, “Tommy, you’ve got two choices: service or college.” And fortunately, college was available to me. I was able to stay with a family member so I did not have to deal with room and board, and I made enough over the summer and vacations to cover most of my tuition.

It was a state teachers college – Indiana State Teachers College, then called, now Indiana University of Pennsylvania, I believe. It didn’t matter to me what it was because I got to go to art classes and found very quickly that I was middle-of-the-road, C student. Although, you know, I’d been a star as art students are when they’re still in high school – the class artist kind of thing. Rude awakening, but I still loved what I learned in my classes.

Looking back, I think part of it was – no, that’s much too much of a conceit – trying to learn the magic that my mother had in hand. But essentially, I was an apprentice artist, so through the classes, learning what I could. And that went on until my senior year. Basically a mediocre student, and I took an elective in sculpture.

Please understand, at that point in time you got three or four electives. They only occurred during your senior year – the rest of your classes were laid out for you throughout. So the professor named Tom Dilla was teaching a class in metal sculpture, and it fascinated me – the thought, possibilities there. And he showed me how to weld and cut metal and said, “Go to it.”

So I whacked out some pieces and stuck them together, and then stuck another one on this – of course this is abstract, non-objective – and how about one there, and then yeah, that looks pretty good. Step back and I walked around to the side and glanced at it and wait a minute – it doesn’t look like I expected. There’s not much back there. I need to figure out a way to keep the look that I like and put more stuff in there so that it works. And at that point, that challenge of getting a piece of sculpture to function 360 degrees, to say nothing of this or this, just lit me up and continues to be an enthusiasm of mine even at my age now.

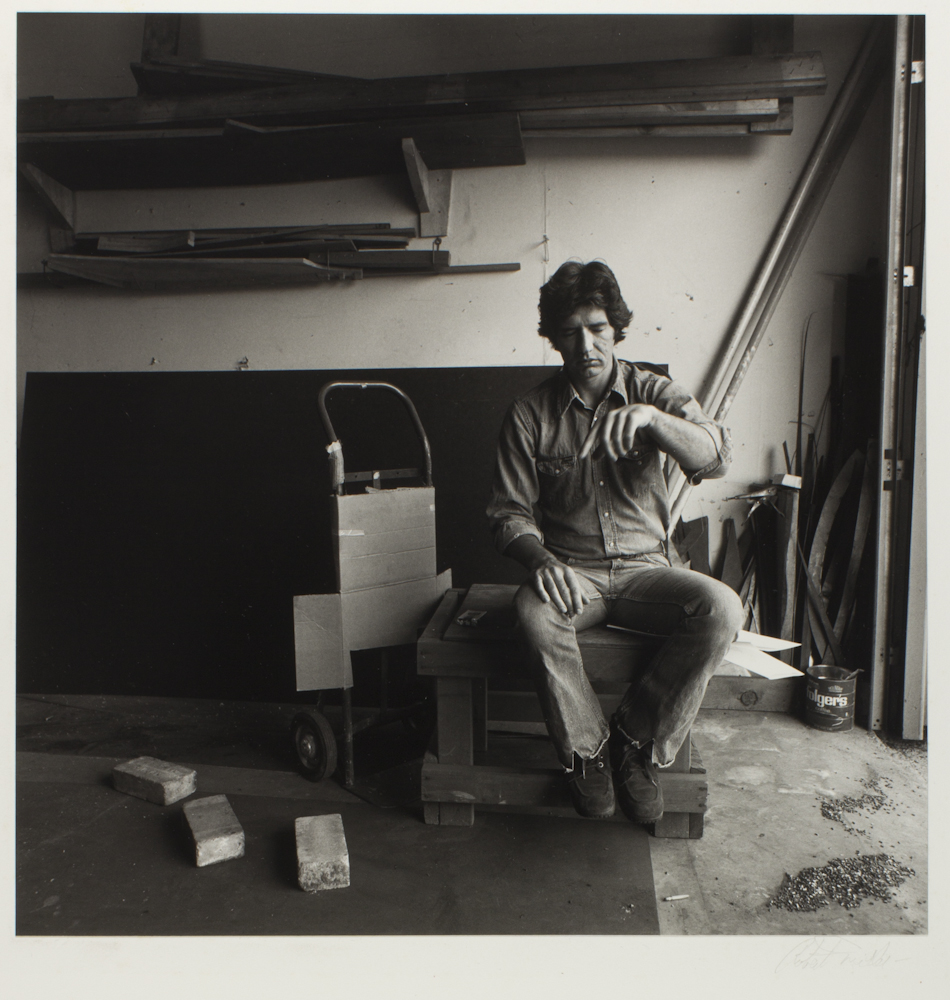

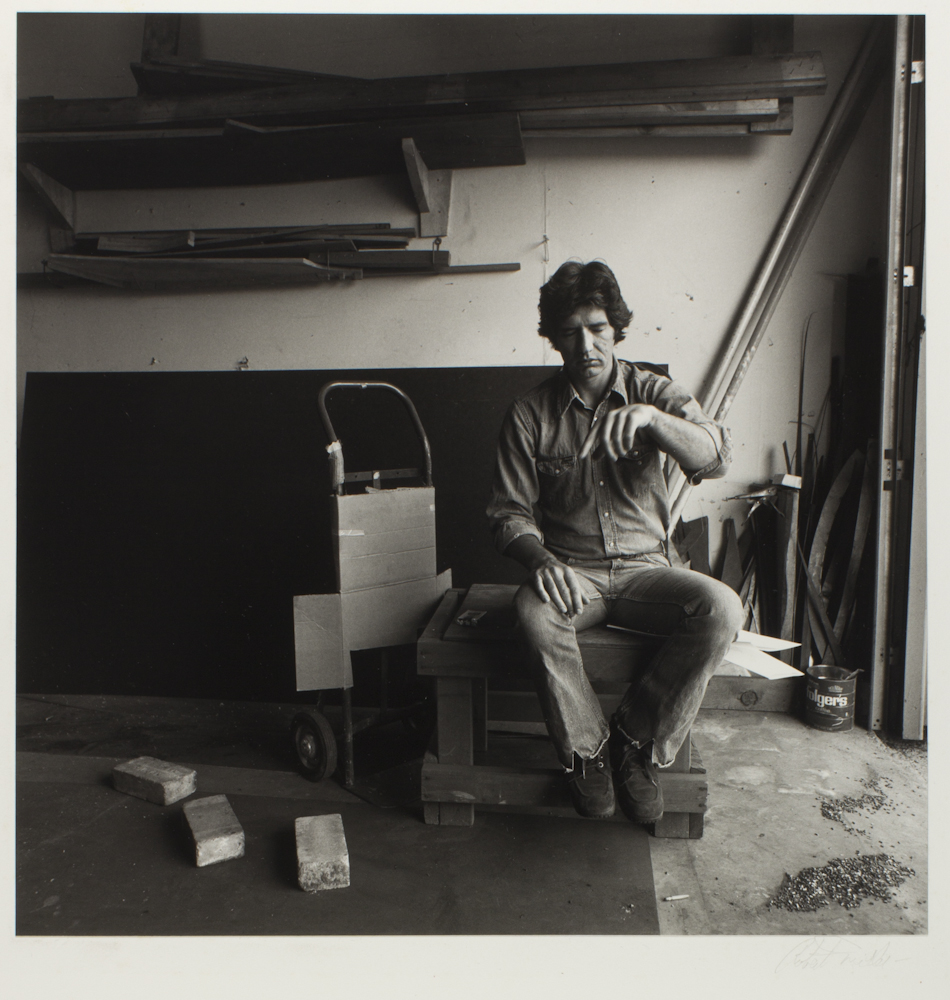

So that’s where I became interested in sculpture per se as opposed to art in general. Went on, well, married after graduation, taught for a couple years in public school system, continued learning metal sculpture at least welding and cutting and so on, went to graduate school in sculpture at Ohio University.

Not what I expected it to be. I was a TA and that was fine – I couldn’t have gone to that particular graduate school if they had not offered me a teaching assistantship. So I spent, you know, a good deal of my time teaching undergraduates, but I found that the meetings I had with my thesis professors – the first was really good, second pretty much rehashing the first even though I had done a different body of work. By the end of my first year, I got a sense that I was being graded more on who I was rather than what I was doing. I was okay, therefore – and this is the ’70s so at that point it was “everything is good, everything is art” and yeah, all right. But I resented it.

I wanted to talk about the stuff that interested me. So I turned the resentment into my graduate thesis show where I produced enough cast work to satisfy any requirements they may have had about any competency I had in metal work, but I fashioned it all into an altar along with a throne. And I cajoled the undergraduate class that I was teaching – Metal One or maybe ten of them – into being my attendants. They all had cast aluminum faces of me with black hoods, and they marched into the gallery which I had transformed into a pseudo-church. So you saw like a dozen of me ranked up in heights with these black hoods on, and then I come up in the end. The whole point of it was, though, I sanctified my name using rituals borrowed from the Catholic service.

I got my degree but that was about it relative to Ohio anyway. I do owe David Hostetler a debt of gratitude though – he introduced me to Jud Kane who was teaching here in Eastern Oregon. He was the chair of the department at Eastern Oregon State Teachers College, now Eastern Oregon University I think. And we met at the College Art Association annual conference in Chicago.

He was looking for basically someone to teach a whole range of undergraduate art classes, and oddly I fit the bill because of my undergraduate education in teaching art in the public school, and that curriculum involved printing, calligraphy, fabrics, to say nothing of drawing, painting. So I was hired there and that’s about all I’ve got for right now.

Young: So talk to me about – so you moved to La Grande, Oregon to teach. Were you familiar at all with the art scene in the Pacific Northwest in the 1970s?

Morandi: Not a bit. But at that point in time, I was so self-involved it didn’t matter. And I’m – that’s the best word for it. But it was not to the extent a self-involvement in me, it was the stuff that really intrigued me – the art, sculpture, the whole thing. That was my focus. I would have taught anywhere, anything, as long as I made enough money to help support my family as well as a studio and art equipment supplies.

So La Grande offered that. In fact, it offered it in spades if you’re looking for someplace with no distractions if you’re not interested in hiking, the outdoor life, or hunting. And it’s a great town to raise my young daughter in. And so I stayed there, off and on – I’m talking about leaves of absence occasionally for commissions – but I stayed there until Colleen graduated and went off to university.

Young: I think it was fairly common for artists at the time, and I don’t know if that’s true today as well, to have a balance between teaching and working on commissions?

Morandi: Very much so. I mean, there are – I’m thinking back to my father’s ultimatum when I graduated – I think there are two more when it comes to art: teach or what was then called commercial art, graphic design today. It is very, very difficult to make a living, an ongoing living in the arts, and to land a job teaching meant a steady paycheck and that gave me the freedom to explore.

But yeah, carrying a full teaching load and making sculpture or doing painting or whatever is pretty standard for a lot of folks in visual arts. And in some ways, in my case, I think it had a great deal of value because it was my socialization, how I – that was my social contact with other people because the rest of the time I was in the studio. And I’m not exaggerating here – evenings if I was teaching through the day, weekends. I took Christmas off and most of Thanksgiving. The rest of the time I was in the studio. I have regrets in that regard relative to raising my daughter, but we’ve talked it out and discussed it since then and it’s okay.

Young: Let’s move to another question. Did you get connected with other artists in Oregon once you were here?

Morandi: Well, my colleagues at Eastern, but other than that, the splendid isolation of La Grande didn’t allow for a lot of that. We didn’t get many artists passing through, and I don’t know if I would have sought them out in any event. I did have a show at the Fountain in I think ’74 of my sculpture.

Young: And for those who don’t know, could you just give some context as to what the Fountain was?

Morandi: Ah, the Fountain Gallery. Arlene Schnitzer – remarkable woman. She opened the Fountain late ’60s. I turned up in the early ’70s, but I asked Jud Kane, my department chair at the time, what was the best gallery in Portland and he said “Fountain,” and so that’s where I went and showed my work.

But Arlene was the force for visual arts in Portland and surrounding areas pretty much her whole life. She had such influence, but it wasn’t – I was going to say it wasn’t – yeah, it was. It was direct. If Arlene wanted something, she would ask or tell, but she did it in such a charming fashion. I’m reminded of a phrase I once heard defining a diplomat: someone who can tell you to go to hell in such a way that you were looking forward to the trip. That was Arlene.

So at the opening, a man named Bill Blicks turns up. He is a sculptor working out of Eugene. He saw the advertisement for my work and liked it, thought he’d like to meet me. Fascinating guy – undergraduate, graduate degrees in physics, I think nuclear physics maybe. Went to Los Alamos, worked there, quit, and when I asked him why, he said those guys understand the language of math with a fluency that I’ll never be able to obtain. So I left and came to Eugene out of the blue, started his undergraduate degree in art architecture – and I don’t know if he got it or not, but he got awfully close to it. Took an elective class in sculpture and all of a sudden architecture and physics – not so much. Sculpture for him, and he went on to get his MFA and settle in Eugene.

Young: Interesting that you had the found in the arts and he had it in the sciences and you meet in the middle with sculpture.

Morandi: Yeah, and you can’t imagine the kinds of conversations that that generated over the years. He’s very well read, articulate, fascinating guy and brimming with energy.

Morandi: Yeah.

Young: So you’re still relatively new in Oregon at this point?

Morandi: Oh yes, very much so. But then so were a lot of other people. And the ’70s were, in terms of openness and acceptance, they were just a little looser, certainly early ’70s, late ’60s and early ’70s. But to go back to your earlier question, I knew, with the exception of Bill, no other sculptors. I knew their work but I hadn’t met them. I, to this day, I don’t know who the other entrants were for the selection committee. I know that there were probably four or five. I’m guessing Lee Kelly was probably one of them because he was certainly the top sculptor in the state at that point. Beyond that, I don’t know.

Young: What made you put together a proposal for this? And this was – did you know at the time that this was Oregon’s Percent for Art program?

Morandi: I was aware it was brand new and they were still sorting out some of the details as to how to administer it. As to my motives, I’m wondering myself because in ’74, directly after that show, I received a commission for Tacoma, Washington – a bronze piece that took two years, more than two years. No, I was still working on it when I submitted for Salem.

I think part of it was Peter Hero and I think maybe John Frohnmayer were very enthusiastic about the program. They wanted to make sure that they got as many good proposals as possible for this first large outdoor piece. I’m pretty sure that that’s the way it happened because I was kind of half-drained after spending two years on one piece to turn around, spend two years again on another. In any event, I submitted.

Young: And I just I’m curious about any of that – if you knew that the piece was going to be attached to the Capitol or if that was your decision, or what a proposal looks like, if you got interviewed, any of those details.

Morandi: The request for entries went out and it stated the site, and I think there were also architects’ drawings with it, the budget. I don’t know if they put a timeline on it at that point or not, but it didn’t really give a whole lot more information. Now please keep in mind this is 46 years ago, so it might have been a little more filled out than that, but that was my sense of it.

And the artists were given free rein to develop any kind of proposal that they felt would work with – that was the east entrance, the back door if you like, to the building – and let go with that. Here’s your budget, what can you come up with?

I know that one of the proposals, it might have been Bruce West, took inspiration from the two marble relief panels that are in the front of the Capitol and did some stainless steel relief panels so there were freestanding at the east entrance. I don’t know what the other proposals were. For me, I was interested in the recessed aspect of the entrance, and thinking – I can’t remember if I just gave a nod to those marble relief panels in the front, but they were basically the building walls, back entrance, a couple of large simple panels here and then some gestural ribbon-like lines that flowed back to that. That’s the one that I submitted and that’s the one that was accepted. It’s not the one that’s on the Capitol today.

You asked about the selection committee. I expect the makeup was then pretty similar to what it is now, which would be the architect for the building, representative of administration of the building, representatives of the building’s users, local artists, general public. I expect I’m missing somebody here – oh, representative from State of Oregon. Everybody who had any kind of a finger to stick in the pie relative to that was on the committee. It’s a very diverse group of people in terms of their backgrounds and interests.

They would look at the entries. I do not recall – I must have though – I do not recall giving them a presentation, that committee of eight or ten people. I probably did. But the presentation I remember much more clearly after the piece was accepted, after the piece was accepted was when certain legislators learned at that point that there was going to be this sculpture on the east entrance to the state building. They wanted to know what it was all about.

Morandi: I don’t, as I say, I don’t recall giving it to the smaller committee, but I did to a joint committee of House and Senate Ways and Means. That was a much larger committee and there were a lot of people in the room in addition to the legislators. I only remember two of them – Peter Courtney and Phil Lang.

In any event, we had about an hour or so to kill. Peter Hero, who was then the executive director of the Oregon Arts Commission, told his assistant Nick – whose name slips me – to take me out to lunch and bring me back, and then I could speak to the group, testify after that. So he did, and we went to a nice place in Salem. I had lunch and I also had a pint, maybe two, of craft brew. Anyway, when I returned I was feeling fine, and I was asked in so many words, “What’s it supposed to be?”

Morandi: I’d like to talk a little more about that in a little bit, but I spoke with them about abstract art. Abstract anything – a legal abstract is a clarification of, if you like, of a large complex legal document. Abstract art is a simplification of forms, although in the case of the legal abstract there’s clarification there too. In the case of art, it can be any number of things.

Think about this – and I think this is what I told them – when I do this [gesture], what do you see? Just angular line, yeah? What if I said deer’s hind leg? What if I do this? Now what do you see? The same thing but maybe a little more flourish. Try a profile of an upper human’s lip. This arrow, or part of one? This same arrow? Maybe a raven’s beak, maybe a spearhead. Okay, that’s the ambiguity of abstract stuff.

And when it is put together in a way that is hopefully pleasing, maybe the viewer will find a deer’s hind leg or an upper lip or a raven’s beak, and find a point of reference to examine the rest of it. The old phrase is you take away from a piece of art what you bring to it.

Young: A Rorschach test?

Morandi: Very well put, yeah. Here’s the thing – if you allow that visual language is as rich and varied as written or spoken language, as is oral language, think about this: You and I talking now, we have no trouble understanding each other. “Illegitimi non carborundum” – to them, yeah, as soon as you move into another language it’s… But incidentally, it means “don’t let the bastards grind you down.”

Wouldn’t you have been impressed if I had…

Young: I would have loved it!

Morandi: Well, here’s the thing though. I mean, if you look a little more carefully into that – “illegitimi,” okay, if you contemplate, think a bit – “illegitimi,” okay, illegitimate. “Non” – non. “Est carborundum” – that’s tricky, but you begin to get some sense of it, but nothing near the context.

That’s what it feels like to be fishing around trying to figure out what a piece of sculpture is. I mean, there are no pieces, no parts of any of that sculpture – the Salem piece that’s on the Capitol – that people have not seen before. They’ve seen everything there, but not in that arrangement.

But if I said okay, Eastern Oregon is well known for double rainbows – first time I ever saw them was when I came here. You take a section of that, flip it over, you have a couple of arcs. The focal point at the back of the sculpture could be a gun sight or it could be a couple of hands. The gestural arm off to the side could be a wing, not a deer’s hind leg certainly, but you see the point I’m making?

I mean, that twist that goes down the side – thinking about this interview a couple days ago, I noticed that that same twist is on the trim on the inside door of my car, starting flat and twisting over. It’s all there, they’re all familiar forms, but they’re put, as I say, in a way that require you to think about it a little bit and look for form relationships in ways that you wouldn’t otherwise.

Let me get back to my original point. Oral language – think about this. Beethoven’s Fifth – not a word in it, but boy can it elicit any range of emotions. But objectively, sounds in the air, that’s all it is. But if you think about how we were raised, at least here in the Western World, lullabies from your parents, music was always there – what your parents were listening to on the radio or these days streaming. The rounds that I hope they still do in school – “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” hymns in church. As you move into your teens, all the popular music there.

I mean, music is informing all of those growth periods and you’re developing fluency in sounds so that as you move through your life, you’re able to say, “Well yeah, I wasn’t into classical at first but I liked that particular – was it Pachelbel?” Yeah, and so on, and the fluency grows.

Visual arts – all kids start out the same way, but mom and dad are not drawing, as mine did, drawing sketches for them. And used to be – I don’t know if it’s still the same – but when a child hits a point, and prior to that, I mean, you give any kid a piece of paper or crayon and they’re happy. “Let’s do this!” Until they feel the need to make something look the way it actually is – five fingers on that hand and a palm. And if they get instruction then, and sympathy and encouragement, maybe they sort themselves through this very difficult thing to draw. Most don’t, and at that point they drop it.

Morandi: As they progress, their visual literacy is functional but it is prescribed only by things that they have seen, or always by things that they have seen. If they haven’t seen it, then it’s not part of their vocabulary. If they see something isn’t part of their vocabulary, they’re going to sort around in their visual words until they find, “Oh yeah, that looks a little like that, maybe. Maybe, I don’t know, maybe not.” But the more they look, the more places they travel, the more things – visual things – they’re exposed to, the broader the vocabulary gets.

Sadly, for most people it stays a functional part of their life and not really much of an aesthetic component in their lives. Hence the suspicions, the indifference, occasional hostility when someone sees something they don’t understand, particularly if government funds are involved. “You mean to tell me my tax dollars paid for that?” I’ve heard that a number of times.

Young: So when they asked you what it’s supposed to be, were they expecting you to have an answer that it’s supposed to be X? Not “it’s whatever you want it to be?”

Morandi: No, no. Exactly, they want – they want to define it in their terms, understandably. And if I explained it to them, well, you know, that’s – I can’t say that’s part of a rainbow, that’s a little too artsy. If I could find something that referenced those forms for them – “Hunter’s gun sight, you see, and little bit of the rifling on the inside, you know.” Although I would not like to be associated with planting a gun sight at the eastern… no, that’s not a good idea at all.

But you see my point – if I can pull it into their reference, they can understand it. If I can’t… You know, that question didn’t exist, “What’s it supposed to be?” until about 100 years ago relative to visual arts. Prior to that, they all had their own narratives, they were easy to understand. Even through the Impressionists – they got a little fuzzy but you could still tell what you were looking at.

And then the Dadaists, Cubists came on scene. I mean, you got Marcel Duchamp signing a men’s urinal and putting it in the gallery and saying that’s art. And you know… but his point was philosophical, not aesthetic as far as I know. “I’m an artist, I define what art is. I say that’s art, therefore it’s art.” The Dadaists were basically nihilists, and if you look at the times, the 1920s and so on, made sense – world wars and so on.

But the Cubists really put it over the top. They’re providing one plane but showing you a profile and a full face at the same time, and then what – where’s the – and the arms and legs are in all these different places. The notion that they’re giving you multiple views of the same subject…

Young: Yeah, that’s fascinating.

Morandi: And to encourage you to explore around. And of course you got those garish colors too and that’s hard to get past. You see the point I’m making – I mean, it’s all asking a lot of the viewer, and the viewer is not inclined to invest that kind of intellectual capital in something that “it’s just art anyway,” you know. But I’m off on a tangent here, I beg your pardon.

Young: No, I love the tangents. I do want to know what inspired the name that you eventually came to – November Sprinter for the piece?

Morandi: I don’t… okay. We spoke of – I spoke of narrative a little while ago. The title is a way of deciphering a piece that may not be easily accessible to the viewer. “Well, what’s it called?” In my case – I can’t speak for others – titles are always afterthoughts, just a way of identifying the piece to a third party or on paper somewhere. In my mind, it’ll always be “the Salem piece” – that’s what I think of it as.

However, I was asked to title it, and it seemed appropriate to call it November Sprinter – November being election month. Politicians wanting to get elected tend to jack up their game a little over the last few days, and hence November Sprinter relative to, let’s say, political aspirations.

Young: Your piece, your proposal was accepted, then the design evolves to what was eventually created. And did that happen while working with the committee or how did that evolution occur?

Morandi: It did, did. Once the piece was accepted, I determined it was much too bland. It really didn’t engage with the building. It was basically ornamental, and I requested and was given permission to develop another design from the committee.

I recently went – I still have all my sketchbooks, they stack I don’t know somewhere between two and three feet high – and I pulled out the ones from the Salem era. There were half a dozen or so. The variations when I started afresh – looking back on that, I mean, they’re pretty astounding. I mean, the drawings are nothing to brag about, they’re the quickest way to get an idea from my head onto a piece of paper.

And there’s one set that I must have pulled out at some point in time that shows a centrifugal piece in the back of this recess section with arms that come out, and then a whole series of drawings that came after that that just kept revising and revising and revising and revising until at the end you have – it’s still basically a symmetric piece, both sides, but those rainbow arcs are there. At some point they just evolved.

As I said, I’ve got four or five sketchbooks filled with ideas, at least two of them have nothing but generative ideas for that next piece. I did a number of models based on those ideas and variations therein. I think I asked the committee to make at least two more, maybe three more exceptions. I’d submit one, they’d say okay, couple weeks later I said I’d like to tweak a little bit and I tweaked a lot and submitted again – okay.

I know that I was testing their patience severely, but I just couldn’t find something that really snapped for me until I finally did and then began in earnest on that. So to finish answering your question, the committee did approve the later adaptations, and I probably started work on it maybe a full four to six months after I was commissioned to do it just because I kept doing the revisions throughout.

Young: When you were presenting the models, were you having to go to Salem each time or did they ever come to your studio in La Grande?

Morandi: No, what I would do, because the committee would meet at certain times – although they did do some special meetings for me – I’d take the models to the Arts Commission in Salem, leave it there, and then when they were finished, they did not ask for proposals or anything like that. I think they did it more informally that way.

In any event, then I’d drive back up, pick it up. At this point in time I should mention I was living in the Eugene area.

Young: Oh, okay.

Morandi: Yeah, I – once again Bill Blicks – I was invited to teach a class at Lane Community College where he taught, and to have a show down there, and I did. So this all happened as part of that. And the studio that I had in La Grande was nowhere near big enough for this Salem piece, so I looked around, finally found an old plywood patch mill in Lowell, what is that, 20 miles east of Eugene, and it was plenty big enough and built the sculpture there.

Young: Talk to me about – I can’t even conceptualize how one would build a sculpture of that size.

Morandi: Well, I reproduced the portion of the wall at the Capitol in plywood, whatever that is, and as I said, it was a big plant and it was abandoned. I got it very cheaply – rented it, I should say. And once I’d reproduced the portion of the wall that I would use, I built what they’re called patterns. I built them with wood – 2x4s, 2x6s, something called Masonite, which is a thin board that will flex, not entirely, but it will flex pretty well. So if you have subtle bends or curves and things, you can nail it down. If you got an arc, make it in, put it in a strong wooden frame and you can tack down this piece of Masonite into that arc.

Morandi: So I do reproduction of – well, first you scaled up and it’s very simple – half an inch equals a foot. Pull carefully off the model this size, enlarge, make a wooden pattern and then make another one and keep going until the piece exists, or at least as much of it as you need to at that point in time, in Masonite and plywood and 2x4s.

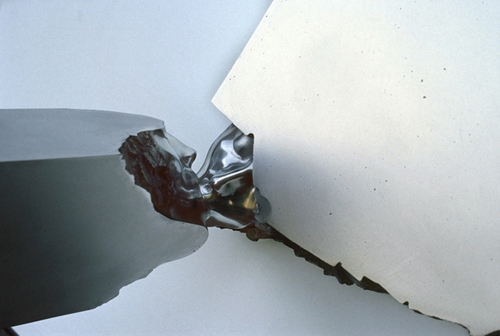

Okay, now to get that into metal – take the piece off the wall, set in a cleared space and determine how many pieces will have to be cast, how many pieces of metal will have to be cast to make this one piece. And I think for – if we stick with the rainbow arcs, I think it was probably four to six pieces, separate pieces of metal that would have to be cast and welded together later.

So what you do then at that point is take – it’s a simple cope and drag mold. It’s a simple two-piece mold and I use something called resin sand. Very simply, you add resin to fine grain sand and then you add a catalyst to that mix it all in a cement mixer. And then take this piece – let’s go with a simple, let’s say a foot square maybe two inches deep, forget the sculpture stuff, we’ll just talk about a simple square form that’s two inches thick.

You ram this stuff over it to three to four inches thick, this resin sand, and before it sets up, walk away from it. Now it’s held in place by a flask, which is brick, so you’ve got a nice border of, oh say, four inches around this square pattern, four inches on top. Twelve hours it sets up, you flip it over, you remove the pattern, take it out carefully and you’ve got a negative print of the top of that square.

Then I took wax, microcrystalline wax – it’s a sculptor’s wax – poured a sheet or poured sheets that were roughly 3/16 of an inch thick. So under a quarter of an inch, and since it was wax you could bend, fold, you could cut it easily. Cut one to match that, set it in there and then cut strips along the side – remember it was that thick. So now you have a wax form with two-inch sides and the whole thing in wax is 3/16 of an inch thick.

Then you put some separating compounds on and so on, and you do this resin sand thing again. You ram up the second half on top of that. So what you’ve got is a resin sand sandwich – you’ve got first piece, the wax pattern on the inside, and then the second piece on top of that. That sets up again, 12, 14 hours. You carefully set it up on its side, find the seam where the two pieces meet – the cope and the drag – carefully take a chisel, tap tap tap tap, pops open. You remove the wax carefully so that when you put it back together you have a hollow, an opening that is the ghost, if you like, of that first square.

Young: Okay, and that’s where you put the metal that you’re using?

Young: You’re doing this all by yourself?

Morandi: I had one assistant most of the time, but yeah.

Young: Is that common for sculptors to be doing each of these components by themselves with an assistant, or are they sometimes commissioning aspects of it to other…?

Morandi: Yeah, traditionally sculptors simply did the – just do the pattern and walk away. Or Dan never cast any of his stuff. Or carve the marbles – that was all done by artisans. But into the ’60s and ’70s, back to earth, the craft movement, it became part of the process to see it all the way through. So that’s how I was educated, so yeah. Every everything on that sculpture I did, or me and my assistant did.

In any event, that was glued back together, clamped, and I was reviewing my sketchbooks and I found an old drawing of how I got those molds from – I’ve got like a ’63 Dodge pickup and I’m using this – and how I got them from Lowell to the foundry at Lane. Since I was teaching there, I had casting privileges. I think there was a spring mattress, yeah, and then a piece of plywood, a three-inch piece of foam, another piece of plywood, and then the mold on top, very carefully strapped in. As many as I could get in the back of the truck – these are delicate molds, a bump and they crack. It’s just glued together sand.

Morandi: Off to the foundry now and into the pouring pit – the place where the molds would go to have metal poured into them. I did these pieces edge up, which was not done at the time because getting back to our square, our slab – bronze is heated to about 2,150 degrees, silicon bronze anyway. That’s the optimum temperature in the furnace. As it comes out, it loses 100 degrees a minute. When it hits 1,850, it freezes. So you’ve got what – 18, 19, 20 – 300, 400 degrees to play with, three or four minutes.

If you’re casting more than one piece, you need to be very aware of and alert to the time as it goes down because you don’t want to spend all that time or see all that time and effort that you spent wasted because the piece – it’s called a short pour. What I did was set the pieces up on edge, clamped them on the sides, poured in through the top so that instead of the metal coming down into the feet and then spreading sideways – not much gravity there – went into the top and gravity took over. So I was able to cast thinner, somewhat larger pieces by casting them edge up.

Young: How do you pick bronze as your preferred metal?

Morandi: Bronze is wonderful. It is a very congenial metal to work with, and it’s, you know, the tradition – to put in, say, an aluminum sculpture up there wouldn’t have the same aesthetic weight, at least culturally speaking, that bronze does. So that was part of it. That and I just really enjoyed working with bronze at that point, still do or did.

So once a piece is cast, open it up, cut off the sprues, that’s piece number one. You cast four or five more, weld them together, dress out all the welds – tada, you’ve got one piece there. I can’t remember – it was either, I’m thinking 56 but it might have been 76 separate pieces that were cast for that.

Young: How long does that take?

Morandi: Months. Takes it – takes a while. The – it’s well, virtually all the time that I spent on the piece was spent casting it.

Young: And are you teaching while you’re working on this piece?

Morandi: Yeah, I kept – I taught one…

Young: Having a family?

Morandi: Yeah, that was… no, sadly we – I spoke earlier of my regrets about my early life with my daughter.

Young: It’s a lot that you’re balancing.

Morandi: Yeah, yeah. But you keep in mind my – I was going to call it passion, more like an obsession at that point, but just a commitment to get this damn thing done.

Young: Yeah, I can’t imagine the scale of it.

Morandi: It’s daunting.

Young: Does each piece get – sorry for getting into the weeds, I’m just fascinated – does each piece get numbered or how do you catalog them to know once you’ve welded these pieces together that you’re putting them into the exact order that you wanted them?

Morandi: Okay, yeah. There’s usually enough variation in each piece, like a puzzle, to show me where they go. If not, I would scratch in the wax on the back “A,” “B” and then arrows just at the point where they came together. And since it was scratched, marked in the wax and cast in bronze so that I would have match points as to where these pieces went together. Was that what you’re talking about?

Young: Absolutely, yeah. So then you’ve – you have these pieces that are prepared and then are you assembling the puzzle together in your studio and then once – are you taking the one completed piece or multiple completed sections of the piece to Salem?

Morandi: No. The process I just described for you is repeated numerous times, and I think in the end I used about a ton of bronze. I’m not sure of that, but it was under a ton because I think they only allowed you to buy bronze in one-ton lots for wholesale, so I can’t imagine I wouldn’t have – I wouldn’t have had the money to buy two tons.

Young: How much does a ton of bronze cost in 19-?

Morandi: Oh, I have no idea. It’s one of the most expensive – I mean, the stuff that I used was called silicon bronze, which means it was 95% copper, 4% silica, and 1% trace metals. Most brass or bronze – 70% copper, zinc, tin and other alloys to soften it. We could go into stories about – I mean, they – that’s neither here nor there though.

They – over the years, the thousands of years that from the Bronze Age, right? They’ve learned a lot and they’ve learned very little. I mean, there’s very little to take away from what I’m doing here as opposed to what they did how many years ago was that – 1200 BC somewhere in there? Ways back. The process is basically the same.

Young: So talk to me about installing the piece in Salem.

Morandi: Yeah, once all the pieces were cast and had – they all had to be mounted to the wall, and they were through holes in that plywood into reinforced sections in the back. This is important to note because when I removed the pieces from the walls of the studio, it left holes in the plywood where each of those pieces would – that became the basis of a template as to where to drill the holes in the marble at the State Capitol.

Well, the marble facade – the slabs are about two inches thick, and then there’s a gap, and then cement wall behind them. The mounting bolts had to go through the marble, cross the gap, and four to six inches typically into the concrete. So that was the first thing – to get the holes drilled using the template, and that was done by a couple of contractors who the state provided, and they did a fine job.

The day that we installed it – rainy January, cold, miserable day. Thinking back, there were, I think, three pickup trucks of pieces of the sculpture, a motley crew, and I mean motley – they were me, believe it or not, shoulder-length hair, beat-up old denims, steel-toe boots. Blicks was there. Bruce Wild, and he had shanghaied his sculpture one class, some of them anyway. So there were about 10 or 12 of us, all disreputable looking, pulled up to the front of the State Capitol in these old pickups and began putting ladders up against the wall and then taking these bronze pieces and sticking them. We were never questioned. That wouldn’t happen today.

But it took us a couple of days to install. Blicks was beyond helpful – his background in physics and engineering, for that matter, made things very simple about installing that. He understood things in a way – “No, just one person, one rope, that 2×6 would be more than enough to hold that, go ahead.” Anyway, the piece was up, was installed, and tada, I guess. That it stayed that way and has stayed that way for the last 46 years.

Young: Was there an event, like a grand unveiling, that kind of thing?

Morandi: No, it just went up.

Young: And then did you ever get any feedback from anyone?

Morandi: No. As we sit here today, from that point until this – now, I think part of the reason was for the first, I don’t know, maybe 20 years there was no name plaque, no title.

Young: Did you sign the piece?

Morandi: No, I never signed sculpture. If I think – I think it’s beyond ego to ruin a good piece of sculpture with a sloppy signature if you’re dealing with form. The second – if it’s good enough, they’ll know who did it. If it’s not, better they don’t. And so maybe it’s the second of those two options would explain why I have yet to hear from anybody…

Young: Though that could be the title of your autobiography.

Morandi: Oh my, yeah. But no, I – as I said, there was no plaque. I don’t know, I don’t know if there’s one now, but I’ve – I’ve done other commissions since then and the same is true even with plaques noting who the artist was.

Young: So then you worked with Blicks – and I have his name as Welson Buckman Blicks III, but he went by Bill?

Morandi: Bill.

Young: And y’all were able to collaborate with another piece in Salem?

Morandi: Yeah, the Sprague Fountain. That competition opened just about the same time that we’d finished the Salem piece. Now please understand that throughout that piece, he even put me up in his guest house for a month or so while I was looking for digs in a place to find my studio. I mean, we were good friends and he gave and helped me install the piece, gave me advice throughout on technical matters and so on.

So when the request for proposals came up for the Sprague Fountain, he said – and we had talked before about collaborating on pieces – he said, “How about this one?” And I was bone tired – physically, spiritually, emotionally, you name it. I just wanted to go back to La Grande and start sorting through all those ideas that popped up about other sculpture while I was spending two years making resin sand molds and pouring them.

But I said, “Okay, here’s the deal – let’s collaborate on the design. If we get it, you do it, ’cause I’m going back to La Grande.” He agreed, and my studio was in Lowell, his was at his home in Eugene, and he came out to Lowell. We took a couple pieces of sheet steel – small ones – started playing around with them and a garden hose and stack up the steel here and there, prop it up or weigh it down and try pouring water over it, beside it, from the side and finally from the bottom.

And the pieces that were arched – the water would hit the bottom and come up and send a spray over like this that we decided was the basis for the design because it just didn’t dump water on top of a piece of sculpture, which so many fountains do. So we left it at that point – he went back to his studio, I stayed in Lowell, and I think it was one week. We gave ourselves a week to do a model based on – and he came back out to at the end of that. Mine and his looked nothing alike with the exception of the principle of coming down and up and under.

We exchanged those models and we each did a second model based on our reaction, response to the first one – simply how can I change this to make it better? We didn’t say that to each other, but it was… yeah. And then we did that again for a third week, and I’m pretty sure there was a fourth. I don’t know if there was any more than that or not, but by the time we had finished, we had, as you can guess, basically two identical models, which is what’s in Salem now – the Sprague Fountain. So it really truly was a collaborative effort in terms of idea generation.

Young: And the funding for that, if I remember correctly, is from the Sprague family?

Morandi: Yeah, it was private.

Young: So what was the selection process like? Was it different or working with…?

Morandi: No, it was – it was the same. I did not go to it because as I said, once it was designed, yeah, I was gone. But Bill told me about it later, and it was the same kind of thing. There were – they had sculptors I think from all over the Northwest, maybe somebody from down in California. They did proposals, they provided models. They – I don’t think they were working models because someone astutely pointed out you can’t miniaturize water. But they did give complete explanation of where the water would go and what it would do and so on.

And Petro Belluschi was one of the jurors. I’m sure someone from the Sprague family was involved, or maybe more. Beyond that, I’m not sure.

Young: This – this relates both to the fountain but also more broadly in your friendship with Bill, but I had read in oral history you – I guess it was when we were talking about doing this oral history – you mentioned this synergy that you had with him?

Morandi: Yeah. I spoke earlier about fluency in languages. He and I shared a visual fluency. It was the sort of thing where we – you – it didn’t require anything but a nod maybe. If, for example, if we were both looking at the same sculpture, he’d look at me, I’d look at him, and we knew exactly what the other one was thinking in terms of its strengths and weaknesses. We just – there.

There was that and, as I said before, he’s a fascinating guy, highly energetic, and it’s very difficult not to get jazzed up just being around him. And the kinds of ideas that he nonchalantly generates are really – “thinks how about that? Think about that.” And to the extent that I processed my version of those ideas and rolled it back to him, then yeah, there was synergy in that regard.

Young: So looking again, going back to the Salem piece, November Sprinter – that was your first Percent for Arts project, but you’ve done others?

Morandi: Mhm.

Young: And were there similarities or differences in those processes?

Morandi: Not really. The selection process remained the same, the selection committee makeup of that remained the same. So, so not really. Things from that day, as far as I know to this, have stayed pretty stable.

I did learn one thing though during the process of those – I learned how to pick the architect out in the room. They are, at least in my experience, the best dressed, the most carefully groomed, the most quietly confident, and the one who emits a quiet but constant aura of energy. That’s in all the cases or all the proposals that I presented to selection committees – that’s what that’s the mean. That’s there. Something – I don’t know if these folks work it out together or if it’s just a certain type of person that gets drawn to that profession.

Young: Is it important as a sculptor to have a visual fluency or literacy with an architect when you’re working on a project?

Morandi: I think so – although I don’t think so, I know so. But in the case of the Percent for Arts that I was involved in, the building was already designed and probably up. So in terms of interacting with the architect and what it was – it was a fair compete. Here’s the space, and the committee decides where the work’s going to go – front atrium, da da.

So it would be nice – Jim Fraser gave me the best insight, I think, though. We were talking about it at some point after and he allowed that he liked the piece and it was okay. I said, “I hear a ‘but’ in your voice,” and he said, “Yeah.” So he said, “Better than marble.” And he was right, but I knew nothing about marble, to farm it out to subcontractors – he would have been ten times over budget and five years in the making, if that. Had to go with what I knew, but that kind of wisdom…

Young: You’ve also been on the other side of the Percent for Arts projects, haven’t you? On the selection process?

Morandi: Mhm.

Young: So talk a little bit about that.

Morandi: There’s an implied hierarchy, although it’s not spoken. The architect, the artists, or those who have a background in art are generally given deference when it comes to their opinions about the quality of a given piece that they are considering for either purchase or commission. That’s not always the case – sometimes the users, depending on how important it is to them – “You’re not putting that in my office” kind of a thing.

So what happens unfortunately more often than it should is that, to my mind – my opinion alone – that work that is adventurous, thought-provoking is often not selected for something that’s safer and a little more accessible. It’s the nature of human beings.

What’s troubling for me these days though – I was recently on an advisory committee to the Percent for Arts folks, and we were asked to take a look at admission relative to admission standards for developing a – what’s the word I’m looking for – stable would be the wrong one – that refers to galleries – a body of available sculptors and artists that could then be – rather than having everybody apply en masse, it would already be basically stockpiled in their records so that it would be easier to communicate with them and perhaps might be able to tailor some of the requests of the selection committee to artists they already worked in that manner, something like that.

What I found troubling was as we reviewed the applicants for that group, that standing group, more than half of them were architectural firms, not sculptors, painters, and… yeah. It’s a convenient marriage – who better to design an ornament for the building than someone who already leans that direction anyway? But when you think of the livelihoods, the – well, all the sculptors who are having difficult enough time already, having to run up against competition against pros who really know how to do proposals and who may well have a better idea in terms of the eyes of the committee. So but you won’t get anything controversial, I guarantee you that. No more “What’s that supposed to be?” on the south entrance to the Capitol.

Young: I want you to tell me a little bit about any commissions that were particularly meaningful to you – they don’t have to be commissions, pieces that you created that were meaningful to you beyond what we’ve talked about in Salem.

Morandi: They’re all incredibly meaningful to me while I’m working on them, and when I work on the next one, it becomes incredibly meaningful to me. I don’t – I hold memories certainly for the Salem pieces – you hear me rambling on today about them. Each of the big commissions has that for me, but meaning…

There was one – we spoke before about the basic indifference, what I found to be indifference to my work anyway, the public work. My – I should preface this briefly by saying in the late ’80s, I simply had run out of enthusiasm for abstract work. I had examined every possible variation in every way that I could and I hit the ceiling.

And my first response was to deal with a longstanding grudge that I had, I suppose, against the general public. But what I decided to do was do figurative work but use all of the standard tropes that everybody thought was so cool, like movie stars, Venus on the half shell, crucifixion and so on. But I didn’t – I did them in such a way as to basically try to show the irony in some of this as well. I’ll show you something later.

So these – these felt good to do. It was nice to be working with organic forms and the figure after so long. I enjoyed it a great deal. That moved into bigger commissions and one was for the city of Aberdeen – timber workers. I did a piece, I think 25 feet high, a tree topper at the top in the process of just finishing lopping off the top of a Douglas fir, a tree feller with his chainsaw partially embedded in the lower portion of the column, and on the other side in high relief as well was a factory worker – bronze patina.

And when it came time for the dedication, I was astounded. They – they had a large recreational center in a park – sculpture was in that park. It was filled, there must have been two or 300 people there. The sculpture was covered in a tarp for the unveiling. I said a few words, other people said a few words, we went out – “ooh” and “ah” – and then I stood in line, which probably maybe 15 minutes or so but it felt like a half an hour, shaking hands. “Thank you so much, thank you so much. I’m glad somebody’s going to be able to see what we did in the years to come.”

I mean, they – there was an emotional bond in that piece because I had taken something that was very familiar and yet very important to them and made it permanent. I’ve – I’ve done a sculpture of it, you know? So when you say special, that is – but for non-aesthetic reasons altogether. I mean, I don’t – the aesthetics of the piece one way or the other and I’m indifferent to it, but the gratitude of the people…

Young: You had also mentioned the piece – and now I can’t remember, it’s at the University of Oregon or Oregon State – the fans and the brick you have?

Morandi: Oh yeah, it seemed like that would be a joyful piece.

Morandi: It was, but it – it was fun to do. Each section – there’s 17 folks or parts of them on each side of that – took a year and a half to do.

Young: Which university is it?

Morandi: Oregon State, at Reser Stadium. Yeah. Those are all Beaver fans – more to the point, I pulled casts off those Beaver fans, life casts.

Young: Wow!

Morandi: And I bought their clothing from them, transferred those – those reverse casts into wax, dress them in their clothes, cut up sections again, cast and so on. But yeah, every one of them is a Beaver fan, some fanatically so, and that was fun throughout. I got to know those folks, enjoyed casting them, and I had them back to the studio after the piece was almost done, ready to be installed on each side, and they’d come and they’d bring their friends and look at themselves. But in terms of any recognition thereafter, no.

No, I remember the then AD – DeCarolis was his name, Athletic Director – explaining, almost apologizing to someone that he was talking about the Percent for Art program – “Well, it’s a mandate,” meaning if I didn’t have to do this, I sure as hell wouldn’t be doing it. And that’s oftentimes the case.

Young: While you were doing these commissions, you were still teaching, and so can you just elaborate – that all works? I guess more so of your work as an educator and if that was important to you?

Morandi: Very, very. Always I – I love teaching. I think part of it was providing the students with a problem and being amazed at the solutions they arrived at, which would not have been mine but were just as valid as anything I could have thought of – in some cases much more exciting. That just – that kind of idea generation and to be able to spark a little bit of that enthusiasm in that student and then to be able to tell them, “Now you get to cast bronze,” and they did, and they learned how to weld.

I don’t know, I’ve got one, two from all those years that I know are still individual artists making it that way. That’s a lot of students who didn’t, and I – sad to say I’m not sure what they’re up to these days, but I hope they’re okay.

Young: Those were the main questions I had for you this afternoon. I don’t know if there were any other topics you wanted to make sure we covered?

Morandi: Yeah, consult the notes and we’re also going to have you walk us through some of your notebooks?

Young: No, yeah, okay.

Morandi: Oh, I know what it is. If someone asked me if there was a basis for the impulse to do this work, I would say it would be an attempt to realize strength and grace in an abstract piece. And when it comes to an explanation, that may be as close as I can get to explaining not only the Salem piece but other work that I’ve done. But then it’s my idea of strength and my idea of grace, so…

Young: And is that why bronze is the perfect medium for you because it has strength and grace?

Morandi: Yeah, but stainless steel can do it as well, just in a different way. It’s got a little more of a fabrication feel to it for that reason, but but yeah.

Young: Like sculpture in general?

Morandi: Mhm.

Young: Okay, well thank you so much.

Morandi: Yeah, you bet. Thank you for your patience.

Artist Site: https://www.tommorandi.net/

Leave a comment